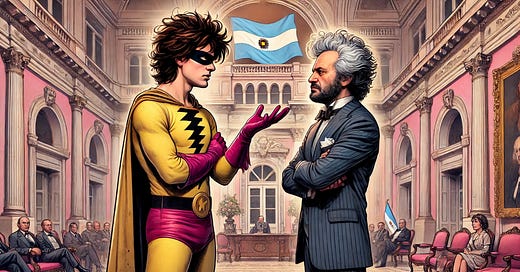

Many countries have recently added a specific law against femicide, meaning the killing of a woman or girl, usually by a relative or intimate partner, on account of her gender. This is to help combat gender based violence. However, Argentinian President Javier Milei recently claimed making femicide a special crime is itself a violation of human rights and he plans to end this law in Argentina. In this episode reformed human rights superhero Shalzed Chazak enters the Pink House, seat of Argentina’s government, to confront Milei about it. For Shalzed’s bio click here.

Yes, I gave up using superpowers. And yes, I do miss them, thanks for asking. But at least I had fun this morning sneaking into the Pink House. I joined a bunch of farmers protesting export taxes and kept shouting ‘sin el campo, no hay pais’ right at the guards so loud they had to arrest me. The funny thing is I just read it off one of the farmers’ signs and I’m not even sure what it means. Then once the guards brought me to one of their little holding cells on the inside I used my extra strength to bust the handcuffs and slip into Milei’s office. Good times.

When Milei’s helicopter finally arrived I was taking a nap. Listen, I was up early to get here and he has a comfortable couch. I went over and watched through the window as the rotors of his Sikorski S-76 slowed to a stop and wondered why the taxpayers of Argentina put up with paying for this every single workday. Why didn’t they demand El Presidente convert some Pink House office into a bedroom, or failing that he could spend at least some of his nights on his very nice office couch?

Milei came in a few moments later, carrying his stylish black briefcase. “What the hell are you doing here?” he exclaimed as soon as he saw me, dropping his briefcase on the floor in surprise.

“It’s been a while,” I said, even though just a few months ago I joined him on his airplane to find out why he called the United Nations a multi- tentacled leviathon for trying to stop hate speech against women.

Two men with communication devices in their ears and hands on their revolvers entered quickly. Probably they were alerted by Milei’s voice and the thud of his briefcase hitting the floor.

“Don’t shoot,” I said, raising my hands slowly. “I’m worried because I’m not a woman.”

“He’s the one that escaped this morning,” one of the guards said. “He was with the crazy farmers complaining about the export tax.”

Milei wrinkled his nose. “You’re here to complain the export taxes are still too high?” he asked.

“No, I’m here to ask why even though violence and murder of women and girls continues to rise, you’ve decided to eliminate the crime of feminicide.”

Milei clicked his tongue and picked up his briefcase, then sat down at his desk. That signaled the guards to relax. “Aren’t you still a human rights defender?” he asked.

What the hell? “No, I push old folks onto train tracks during the day then rob banks at night,” I said.

“Well then that explains it,” he replied. “You see, I’m in favor of equality. I believe the murder of a woman should be punished the same way as the murder of a man. But I guess when you gave up being a superhero you also decided sexism and discrimination would become your new calling.”

No one talks to me like that. “And I thought someone who cares about equality might want to do something about the fact that women suffer an overwhelmingly disproportionate amount of gender based violence,” I told him.

One of the guards said something to Milei in Spanish, and Milei raised a palm for him to wait. “Eres mas lento que una tortuga,” I said to the guard. It means you’re slower than a turtle and it was the only Spanish insult I knew. He said something back I couldn’t understand which started the other guard laughing.

“You know what I don’t understand about the human rights folks?” Milei asked me. “They’re clamoring for femicide laws even though it’s already been proven that they have no effect.”

I sighed. I knew Milei wasn’t stupid, so why was he pretending to be? It’s true no law adding a few more years of jail when a guy murders his wife or girlfriend over the punishment for a regular homicide can really succeed at deterring those crimes, but femicide laws still make plenty of difference. “Femicide laws do work,” I told him. “Without them, we wouldn’t even know how common it is for men to kill their intimate partners and so we’d be less able to take steps to prevent it. Only with femicide as a separate crime can we begin to compile accurate statistics, let alone have effective prosecution and conduct appropriate investigations.”

“That’s my point,” Milei said, smiling and raising his palms like he had been proven innocent. “I’m not anti-women and I don’t condone domestic violence. But what we need here is more awareness, more data, and better police work. Not laws that result in discrimination.”

I sat down on his comfortable couch. A woman dressed in a stylish beige skirt and matching sweater came in and announced that ‘El Ministro Mariano Cúneo Libarona’ had arrived for his appointment.

“I think it’s time for you to go,” Milei told me. Both the guards stepped in my direction, grinning and arms outstretched.

“Isn’t Mariano the minister of justice?” I asked, remaining seated. “If so I should stay, I think both of you might need my advice.”

“I’m pretty sure my guards would enjoy dragging you out the door and tossing you onto La Pirámide de Mayo. And I’d enjoy watching,” Milei said.

There’s no way I’d let those goons touch me, but there’s a Chinese proverb about not overstaying your welcome that I take seriously so I slowly stood up. “Fine. Just tell me one thing. Sixty percent of women who are murder victims turn out to have been killed by a member of their own family. It comes to around 140 women per day worldwide. So you really think removing femicide as a crime is a good idea?” I asked.

Ministro Mariano walked into the office, I recognized him easily due to his distinctive grey hair. “Did I hear people talking about our plan to reassert that no life is worth more than another by removing femicide from the penal code?” he asked.

I wanted to wipe the smug grin from his face. “If no life is worth more than another, maybe governments should take more action against a serious form of violence that usually goes unreported and unpunished simply because the victims are women,” I said.

“Femicide is just woke culture gone crazy,” he replied.

I had honestly been about to leave, but now I decided to sit back down. “Protecting women from being killed is woke culture?” I asked, folding my arms against my chest.

“Femicide started off meaning just the murder of a woman or girl by an intimate partner or member of her family,” Mariano said. “But did you see that your friends at the United Nations have now added eight more categories (p. 12)? One of them is even ‘women working in the sex industry’. Imagine that- killing a police officer, bank guard, or guy that got the promotion you’d been after at the office is one thing. But according to UN Women, killing a sex worker is a new, especially serious crime.”

“Maybe because men think that killing a sex worker won’t be taken seriously by the police and so is easy to get away with,” I said. “Don’t you two equality brothers believe sex workers have a right to life?” I asked.

“La Pirámide,” Milei said, gesturing to the guards.

I stood up and took a step towards the exit. “Did you know in the Jewish tradition each morning men say a special blessing to thank God for not creating them a woman?”

“Well that sounds rather sexist,” Milei remarked.

“Pure patriarchy,” Mariano added.

“It came from living in a world where men felt one hundred percent entitled to murder wives and daughters that defied them,” I said. “Sounds like that blessing might make a comeback here in Argentina. Would you like some copies?”

“Thanks for the religion lesson,” Mariano told me.

Milei made another gesture, and both guards stepped briskly towards me. I slipped between them and out the door so I wouldn’t wind up with more of their germs on my clothing. The woman in beige was standing there, hands on hips, and she pointed me towards the exit.

I went out into Plaza de Mayo and saw that the farmers had already dispersed. Maybe all they wanted was to wave their signs as Milei’s helicopter landed and then they had to get back to their crops.

I sized up the pyramid in the center of the plaza. Even if I had let the guards carry me out there’s now way those two could have lifted me over the high fence around it, let alone dragged me up. I strolled over and took a closer look. I noticed the statue on top is the figure of a woman, and according to the sign she’s supposed to represent liberty and freedom. Sorry to tell you, I think she’s got a long way to go.

Discussion questions:

1. Codifying femicide as a crime seeks to punish certain murders of women more harshly than the murder of men. Is this necessary to protect women from gender based violence, to which they are uniquely vulnerable? Or is it an affront to the principle of equality that is fundamental to all human rights?

2. Femicide is intended to cover situations in which a woman or girl is killed specifically due to her gender. But countries that have enacted these laws have used a wide variety of definitions. Some include the killing of a woman in the context of sex-work, human trafficking, denial of reproductive rights, domestic abuse, female genital mutilation, and more. Is it possible to establish a clear and effective definition for this crime?

very interesting questions to talk about